The problem of fake art still plagues honest art dealers who must deal with the damage caused by the proliferation of fraudulent art in the market place. Although “caveat emptor” remains good advice for prospective purchasers of art, it is also true that sellers of art must be careful how they conduct sales transactions. The arrest and prosecution of a Los Angeles art dealer illustrates that one can be held criminally liable for selling fake art. While anyone can inadvertently sell a fake artwork, a subsequent criminal investigation will attempt to ascertain what the dealer knew or should have known about the art at the time of the sale.

The problem of fake art still plagues honest art dealers who must deal with the damage caused by the proliferation of fraudulent art in the market place. Although “caveat emptor” remains good advice for prospective purchasers of art, it is also true that sellers of art must be careful how they conduct sales transactions. The arrest and prosecution of a Los Angeles art dealer illustrates that one can be held criminally liable for selling fake art. While anyone can inadvertently sell a fake artwork, a subsequent criminal investigation will attempt to ascertain what the dealer knew or should have known about the art at the time of the sale.

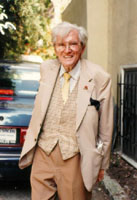

In this case, Raymond March, 73-years old, advertised various pieces of art in the classified section of the Los Angeles Times. On four separate occasions, he sold a total of seven pieces of art to people responding to his ads. All seven were later determined to be fake. The “art” was purportedly signed by well-known California plein air artists Emil Kosa, Jr., Alson Clark, Jack Wilkinson Smith, and others.

A police sting operation was initiated during which Ray March tried to sell additional fraudulent artworks to a businessman. Part of Ray’s scam was using his longevity to lend credence to his claim that he bought the Emil Kosa, Jr. watercolors directly from the artist before his death. A check of estate records, auction records and the artist’s family revealed this assertion to be false. Another eighteen artworks were seized from Ray’s car and home. Most of these were determined to be fake. Some still had labels attached with the word “fake.”

Ray could not provide any business records showing where he had obtained any of this art and claimed he could not remember where they came from. However, detectives were able to trace some of these items and discovered Ray was buying art at prices far below what one would expect to pay for authentic art by known artists. For example, an unsigned work was purchased for $140 and then offered for sale as an authentic Jack Wilkinson Smith for $2,000.

Although Ray claimed he obtained these pieces from many different sources, they were all similar in how they had been transformed into fakes. The artworks neither copied existing works nor the style of an artist. Signatures of well-known artists were added to already existing works that appeared to have been retouched and enhanced.

Ray also claimed he was unaware that any works he has ever offered for sale were fake. However, a check with major auction houses and art dealers revealed a trail of fraudulent artworks rejected over the years. In one instance, Ray consigned an Emil Kosa, Jr. watercolor to a gallery in Orange County. When the gallery had the artwork authenticated and learned it was fake, the piece was returned to Ray who then sold the piece as authentic to a gallery in Santa Barbara. That gallery had the piece authenticated and learned it was fraudulent and returned the piece to Ray, informing him it was fake and demanding reimbursement. Ray then tried to sell the same fake piece as an authentic Emil Kosa, Jr. during the police sting operation. In fact, it appears Ray began placing newspaper ads to find less knowledgeable people to dispose of the art because these pieces had been rejected by dealers in the art community.

Ray also claimed he was unaware that any works he has ever offered for sale were fake. However, a check with major auction houses and art dealers revealed a trail of fraudulent artworks rejected over the years. In one instance, Ray consigned an Emil Kosa, Jr. watercolor to a gallery in Orange County. When the gallery had the artwork authenticated and learned it was fake, the piece was returned to Ray who then sold the piece as authentic to a gallery in Santa Barbara. That gallery had the piece authenticated and learned it was fraudulent and returned the piece to Ray, informing him it was fake and demanding reimbursement. Ray then tried to sell the same fake piece as an authentic Emil Kosa, Jr. during the police sting operation. In fact, it appears Ray began placing newspaper ads to find less knowledgeable people to dispose of the art because these pieces had been rejected by dealers in the art community.

When the District Attorney’s Office considers a case for prosecution it reviews the total circumstances surrounding the crime. In this case, Raymond March sold and possessed a large amount of fake art. He maintained no business records and could not show where he had obtained the art. The fake pieces were similar in how they were created. He bought art purportedly by distinguished artists for ridiculously low prices – prices that one normally cannot obtain authentic works. After an artwork had been determined  to be fake, he repeatedly tried to resell it to someone else as authentic. His false and inconsistent statements showed a consciousness of guilt. Finally, Ray had a poor reputation with art dealers, galleries and auction houses who had dealt with him for over four decades.

to be fake, he repeatedly tried to resell it to someone else as authentic. His false and inconsistent statements showed a consciousness of guilt. Finally, Ray had a poor reputation with art dealers, galleries and auction houses who had dealt with him for over four decades.

While any one of these factors may not have been compelling in itself to prove criminal intent, the totality of the circumstances convinced both the police and prosecutors that the dealer had clearly defrauded others and knew, or should have known, that he was selling bad art. As a result, this dealer was arrested, jailed, and later pled guilty to four counts of grand theft. In this case, let the seller beware.