Sam, a gentleman in his 80s, was an art collector living in New York. He was fortunate to have obtained many fine artworks early in life. Much of the art had greatly appreciated in value over the years. Now retired, he could enjoy these exquisite pieces that had become familiar old friends in his home.

Sam, a gentleman in his 80s, was an art collector living in New York. He was fortunate to have obtained many fine artworks early in life. Much of the art had greatly appreciated in value over the years. Now retired, he could enjoy these exquisite pieces that had become familiar old friends in his home.

This all changed one day when Sam returned home to find his home burglarized. Someone had pried open a window with a crowbar that was left at the scene. Despite police efforts to find physical evidence at the scene or witnesses who may have seen something, no fingerprints, witnesses or leads were developed to solve the crime and locate Sam’s art.

The thief had stripped the home of artworks by Picasso, Miro, Chagall, and Richard Hayley Lever. As time passed by, the police investigation eventually ground to a halt. However, Sam outraged at the loss and feisty by nature, began his own search for the stolen art. Sam made his own flyer and began papering the country with it, mailing it out to auction houses, galleries and art registries. One of these flyers went to a major auction house in Los Angeles.

The thief had stripped the home of artworks by Picasso, Miro, Chagall, and Richard Hayley Lever. As time passed by, the police investigation eventually ground to a halt. However, Sam outraged at the loss and feisty by nature, began his own search for the stolen art. Sam made his own flyer and began papering the country with it, mailing it out to auction houses, galleries and art registries. One of these flyers went to a major auction house in Los Angeles.

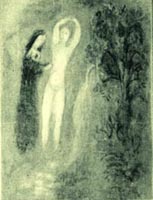

About a year after the crime, the L.A. auction house received a consignment from a man in New York. He consigned an unframed Picasso aquatint from the Vollard Suite entitled Minotaur Aveugle Guide par une Fillette Dans la Nuit, 1934. The rare print was now valued at $50,000.

Kelly, who worked in the Fine Print Department of the auction house, recalled Sam’s flyer. She compared the information on the flyer with the consigned print and realized that the print might be Sam’s Picasso. She notified Detective Mike Guardino of NYPD, who was handling Sam’s burglary investigation, to inform him of the possibility. Guardino told Kelly that it was important that the consignor not be tipped off about the police investigation until the matter could be delved into further. Guardino then asked for the assistance of LAPD’s Art Theft Detail.

The art detective soon learned that Kelly was in hot water with the attorney for the auction house who berated her for giving information to the police. The detective recalled there had recently been a police raid on the auction house to recover stolen property that the attorney would not give up. During a testy conversation with the attorney about the Picasso, it was plain that he was more concerned about protecting clients than the prospect that someone might be laundering stolen goods through the auction house.

The art detective made several appointments to meet with Kelly and examine the Picasso. However, the meetings were postponed at the insistence of the attorney and a vice president of the auction house. The detective later learned that during the delays, the attorney had taken it upon himself to do some amateur sleuthing by contacting the New York consignor of the print and informing him that police were conducting an investigation into the Picasso. This civil attorney decided to make himself the arbiter to determine if the print was stolen and whether the consignor was criminally culpable.

The art detective made several appointments to meet with Kelly and examine the Picasso. However, the meetings were postponed at the insistence of the attorney and a vice president of the auction house. The detective later learned that during the delays, the attorney had taken it upon himself to do some amateur sleuthing by contacting the New York consignor of the print and informing him that police were conducting an investigation into the Picasso. This civil attorney decided to make himself the arbiter to determine if the print was stolen and whether the consignor was criminally culpable.

Ordinarily, the detectives would first ascertain if the print was part of the loot taken from the victim. If so, they would have tried their best to recover the rest of the high value artworks stolen during the burglary. This might involve serving a search warrant on the suspect’s residence or conducting a surveillance to determine the location of the remaining pieces. By alerting the suspect, the attorney allowed him time to conceal the other pieces.

One of the most important stages in a criminal investigation is when a suspect is questioned about the incident for the first time without warning. Criminals often make inconsistent and implausible statements because they have not had time to construct a cohesive story to explain their actions. By tipping off the suspect, the attorney allowed him time to rehearse a story that might sound plausible, knowing he would soon be interviewed by the police.

One of the most important stages in a criminal investigation is when a suspect is questioned about the incident for the first time without warning. Criminals often make inconsistent and implausible statements because they have not had time to construct a cohesive story to explain their actions. By tipping off the suspect, the attorney allowed him time to rehearse a story that might sound plausible, knowing he would soon be interviewed by the police.

The suspect was now given time to fabricate documents. The attorney asked for proof of ownership and the suspect later faxed back a generic do-it-yourself receipt that can be obtained at any stationery store. The suspect purported that he bought the Picasso from some guy on the street.

By interfering with the police investigation, the attorney caused immeasurable damage to the criminal case. He also made himself a percipient witness subject to subpoena in any subsequent court proceeding.

When the art detective was finally allowed to examine the Picasso print, he was confronted by a difficult challenge. The print was part of an unnumbered edition consisting of 250 prints made in 1934. Each print had the exact same image on the exact same type of paper – all signed by Pablo Picasso. How could the detective determine if this print was the one taken in the burglary of Sam’s house when there are 249 others exactly like it?

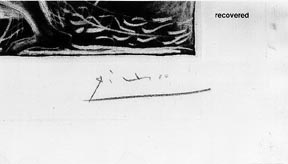

Fortunately, Sam still possessed an old photograph that he had taken of the framed print hanging on his wall before the burglary. Various parts of the photo were scanned into a computer under high magnification. One area of interest was Picasso’s signature. When Sam took his flash photo of the glass covered print, a flash hot spot washed out the area of the signature. Despite this, through manipulation of the computer image, a blurry enlargement of the signature was finally developed.

Fortunately, Sam still possessed an old photograph that he had taken of the framed print hanging on his wall before the burglary. Various parts of the photo were scanned into a computer under high magnification. One area of interest was Picasso’s signature. When Sam took his flash photo of the glass covered print, a flash hot spot washed out the area of the signature. Despite this, through manipulation of the computer image, a blurry enlargement of the signature was finally developed.

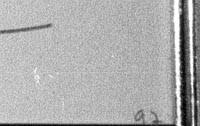

In addition, the detective noted what appeared to be a handwritten number in the lower right corner of the print. Part of the number was cut off by the frame. At first glance, it appeared to be the number “92” that may have referred to the plate or image number used to make the print out of the estimated 100 separate images used in the suite. It was theorized that sometime after the print was made, someone wrote this number in the corner as a reminder of which image it was. There was no record that any of the similar prints from this edition had this notation. Therefore, it appeared to be a unique marking that could help to identify Sam’s Picasso.

In addition, the detective noted what appeared to be a handwritten number in the lower right corner of the print. Part of the number was cut off by the frame. At first glance, it appeared to be the number “92” that may have referred to the plate or image number used to make the print out of the estimated 100 separate images used in the suite. It was theorized that sometime after the print was made, someone wrote this number in the corner as a reminder of which image it was. There was no record that any of the similar prints from this edition had this notation. Therefore, it appeared to be a unique marking that could help to identify Sam’s Picasso.

However, upon examining the actual print from the New York consignor, there was no similar number visible. But a closer look at the artwork revealed a disturbance in the surface of the paper in this same corner. The detective took a series of photos of this spot using oblique lighting and a macro lens. Additional photos were also taken of Picasso’s signature.

However, upon examining the actual print from the New York consignor, there was no similar number visible. But a closer look at the artwork revealed a disturbance in the surface of the paper in this same corner. The detective took a series of photos of this spot using oblique lighting and a macro lens. Additional photos were also taken of Picasso’s signature.

The detective managed to locate images of 16 of the remaining 249 Minotaur prints from this same 1934 edition. Characteristics of these 16 would be compared to details visible in the auction house print as well as to the photo of Sam’s framed print.

The photographs were taken to an aerospace corporation in El Segundo that performs detailed photo imaging analysis for the U.S. Air Force. All of the various images were fed into a computer.

A photo analyst enhanced images taken of the lower right corner of the auction house print. This was where a disturbance of the paper surface was noted earlier. The analyst was able to make visible an erasure made to a pencil notation in this corner. This clearly showed that someone erased the number “97” from the Picasso aquatint submitted to the auction house by the mystery consignor in New York. The notation exactly matched the visible portion of the number on Sam’s photo. What was originally thought to be a “92” was actually a “97” with a European-styled 7 mistaken for a 2.

A photo analyst enhanced images taken of the lower right corner of the auction house print. This was where a disturbance of the paper surface was noted earlier. The analyst was able to make visible an erasure made to a pencil notation in this corner. This clearly showed that someone erased the number “97” from the Picasso aquatint submitted to the auction house by the mystery consignor in New York. The notation exactly matched the visible portion of the number on Sam’s photo. What was originally thought to be a “92” was actually a “97” with a European-styled 7 mistaken for a 2.

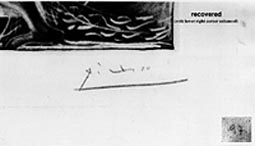

The photo analyst next took the image of Picasso’s signature on Sam’s photograph and corrected distortions caused by the angle in which the photograph was taken as well as the size of the image. Measurements were taken showing the exact position of various points in the signature in relation to the edges of the Minotaur image above it. These were then compared to the same reference points on the 16 similar prints from the same edition that had been collected. The examination disclosed wide variations in how and where Picasso signed his name on each print. This was further demonstrated by creating a series of transparent overlays. There was only one signature that exactly superimposed over Sam’s photograph of the stolen print – the one on the auction house print.

The Picasso print at the auction house was conclusively proven to be the one stolen from Sam during the burglary. It was seized and sent to NYPD as evidence pending criminal charges against the consignor who claimed he bought the print long before the burglary occurred. Ultimately, Sam will be reunited with his Picasso.

It should be noted that the lengthy and expensive process of identifying the print could have been avoided. A close examination of the recovered print revealed small aberrations and abnormalities caused by 62 years of wear and tear. These included water damage on one edge of the print, areas of discoloration on the back, and the distinctive manner that the print was still secured to the original matting. These small, inconsequential characteristics actually made the print unique and identifiable. But, since none of these characteristics were ever noted, they were useless in helping the victim establish ownership.

A victim could even devise a hidden marking system to prove ownership. If Sam had told detectives that he had placed a small pencil dot on the back of his print in the upper right corner and a similar dot in the lower left corner, that would have been all the proof necessary to show the print belonged to Sam. Even if the burglar noticed the dots, he probably would not have attached any significance to them.