The elderly Hungarian couple entered the Csardas Restaurant in Hollywood to share good food with a friend. They had fled communist Hungary after the war, bringing the few valuables they were able to salvage. One of the items was a small painting that had been in the family for 200 years. It was purportedly by Francisco Goya.

The elderly Hungarian couple entered the Csardas Restaurant in Hollywood to share good food with a friend. They had fled communist Hungary after the war, bringing the few valuables they were able to salvage. One of the items was a small painting that had been in the family for 200 years. It was purportedly by Francisco Goya.

Inside the restaurant, they met Gabor Eordogh who was another Hungarian immigrant who had earlier befriended them. Gabor offered to have the painting cleaned so they let him borrow this family heirloom. He left the restaurant with the painting – which promptly disappeared.

The elderly couple spent years trying to locate their painting. During this time, the husband died. The wife, now in her late 70s, delayed making a crime report. She had grown up in a communist regime and was distrustful of the police. In addition, Gabor threatened to destroy the painting if anyone tried to recover it.

LAPD’s Art Theft Detail was finally contacted three years later. They determined that Gabor was a transient who lived out of motels and had no identification, credit cards, or visible means of support. He used a mail drop box for an address and did not own a car. They also learned he was a fugitive who had a pattern of betraying people who trusted him.

In Hungary, eight years earlier, Gabor rented a room from a man. They later took a taxi to a night club for a relaxing evening. Gabor slipped out of the night club and hurried back to the apartment where he broke into the man’s safe and took 10 million forints. Gabor fled to Italy and later entered the United States as an immigrant refugee. Hungary issued a warrant for his arrest and wanted to extradite him. As a result, the U.S. Marshals and the Immigration and Naturalization Service began to actively search for Gabor.

Detectives learned that Gabor already had a prior arrest in Los Angeles. He befriended an older woman, twenty years his senior. He moved in with her and in the role of a lothario, gained possession of her jewelry and promptly pawned it. He was arrested for grand theft but the District Attorney’s Office refused to prosecute.

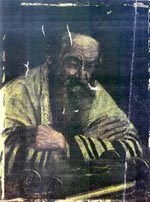

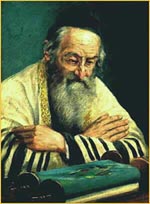

As detectives tried to locate Gabor, they learned that he was trying to aggressively market the stolen artwork, representing it as his property. He assumed the guise of royalty, representing himself as a Hungarian count. He adopted the name of Count Gabor Eordogh de Turul and developed a website for a sham entity called the Solo Goya Institute where he displayed the stolen painting, now calling it El Famoso Rabino. The website displayed his coat of arms and other artworks that did not belong to him. He also created a colorful history for himself filled with castles, secret agents, Nazis, and heroic events attributed to his family. A fictional count grandfather who repeatedly escaped from a Russian POW camp. A fictional countess grandmother who –

As detectives tried to locate Gabor, they learned that he was trying to aggressively market the stolen artwork, representing it as his property. He assumed the guise of royalty, representing himself as a Hungarian count. He adopted the name of Count Gabor Eordogh de Turul and developed a website for a sham entity called the Solo Goya Institute where he displayed the stolen painting, now calling it El Famoso Rabino. The website displayed his coat of arms and other artworks that did not belong to him. He also created a colorful history for himself filled with castles, secret agents, Nazis, and heroic events attributed to his family. A fictional count grandfather who repeatedly escaped from a Russian POW camp. A fictional countess grandmother who –

“True to her noble bloodline and steel backbone, she oversaw the raising and formal education of the present Count E. de Turul. Teaching him all she knew of humanity, instilling an unquenchable thirst for knowledge in all things, especially art and music. Countess Etellica taught him to never forget who and what he is and the long line of noblemen and women he now embodies and must forever represent.”

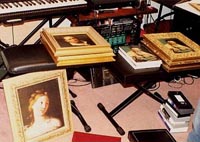

Part of Gabor’s scheme was to sell cheap reproductions of the stolen painting, representing them as limited edition prints –

“Because of the intimate handling Count of Turul has enjoyed with the little masterpiece, he has sensed the whisperings of Goya, Rembrandt and Durer, urging him to complete their dreams of bringing fine art to the whole of mankind. It is his fervent desire that this first limited edition of “El Famoso Rabino” reproduced on canvas, will bring to the homes and places of meditation and worship of all who own them, the radiation of the Great Master’s message and the ageless wisdom of the Rabbi….”

“Because of the intimate handling Count of Turul has enjoyed with the little masterpiece, he has sensed the whisperings of Goya, Rembrandt and Durer, urging him to complete their dreams of bringing fine art to the whole of mankind. It is his fervent desire that this first limited edition of “El Famoso Rabino” reproduced on canvas, will bring to the homes and places of meditation and worship of all who own them, the radiation of the Great Master’s message and the ageless wisdom of the Rabbi….”

During a surveillance of some of Gabor’s family members, the Art Theft Detail was led to a nondescript apartment in North Hollywood rented in another person’s name. The location was further surveilled over a period of days until Gabor was finally recognized exiting the apartment.

Detectives conducted a raid on the apartment one morning while Gabor was having his hair dyed on the front porch. They learned that the “Count” and his family were all stuffed into a single bedroom of a two bedroom apartment shared with a man connected to L.A.’s porn industry. The stolen painting was discovered hidden in a briefcase. Gabor was arrested on state charges as well as the pending Hungarian extradition hold.

A search of paperwork and e-mails at the apartment uncovered another victim of theft. Gabor had hoodwinked a widow in Illinois into investing her life savings to finance an appraisal of the stolen painting. She had used settlement money from the death of her husband from asbestos poisoning as well as borrowing additional money from family members. She was pressured to quickly invest the money to take advantage of a fictitious window of opportunity in order to recoup huge earnings on her investment.

The widow had wire transferred the money into Gabor’s account on the same day as Gabor’s arrest. This was lucky for the widow since Gabor was the only designated signatory on the account and could not access the money from his jail cell. However, detectives later learned his wife had an ATM card and siphoned off the maximum allowed each day until detectives froze the account.

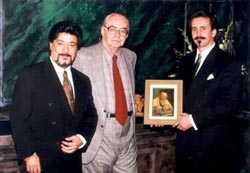

Detectives learned the widow had been further dazzled by a professionally made video to help market the stolen painting. The tape opened with Gabor’s roommate from the porn industry identifying himself as Count Eordogh’s “attache.” He introduced a man named Dr. Rolph Medgessy who claimed to be an art expert. With the “Count” standing nearby posing as the owner of the painting, Medgessy enthusiastically proclaimed the painting to be an authentic undiscovered Goya. He said he determined this by detecting hidden micro-signatures placed on the painting by Goya himself. During his interview with Gabor’s “attache,” he claimed to have “3-dimensional vision” that allows him to see numerous hidden micro-signatures on the painting that most average people cannot detect.

This was not the first time that Medgessy’s name had popped up on a criminal investigation. During the same year, an art dealer in Palm Springs complained that she had been conned by Medgessy who wanted her to sell 251 artworks he owned in New York. The art was mainly works on paper by artists such as Matisse, Modigliani, Calder, Church, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, and Goya. Medgessy claimed he had authenticated all of the art himself. After selling much of the art to clients and showing it to other experts, she learned that the artworks were fakes. Some were exact copies of known works and others were made in the style of an artist. Medgessy lived in Montreal, Canada and operated a business called the Institute for Discovery & Documentation.

Detectives learned that Gabor had repeatedly tried to sell the stolen painting for millions of dollars. However, he had difficulty authenticating it – even contacting the Prado in Spain at one point. Eventually, Gabor settled on a sophisticated scheme to use the painting as collateral on a multi-million dollar bank loan. This was to be accomplished through a spurious authentication by Medgessy along with an appraisal by a man who primarily conducts business through an internet website. To make the deal appear more legitimate, Gabor tried to insure the stolen painting for $75 million. Medgessy authenticated it. Gabor provided phony provenance for the artwork, claiming it was owned for centuries by his distinguished family. Finally, a broker was lined up to find a lender using the bogus paperwork.

When the painting was recovered, it appeared decidedly different from when it was stolen. It had been fully restored. The black soot had been removed and damage had been repaired. To preclude Gabor from claiming the painting was not the same artwork, it was examined and photographed under ultraviolet light. This clearly revealed the restoration done at each damaged portion of the original artwork. The examination also revealed the name “Y. Dohnal” in the upper right corner of the painting.

Detectives were unable to locate anyone in the art world who believed the painting was by the hand of Goya. Despite this, Gabor was still prosecuted for the theft of the artwork although it may be valued as mere decorative art.

The court battle was often contentious and combative. Some of the characters resembled the cast from a Fellini movie. If Gabor’s appearance is any guide, Hungarian counts wear pink socks, a pirate-like drawstring shirt with puffy sleeves, a velvet brocade vest, pin-striped pants, and have long flowing hair. A pro bono private investigator for the defense paraded a micro-miniskirted girlfriend in front of a dumbfounded courtroom. An exasperated gun-toting judge repeatedly admonished the defense attorney, Steven Szocs, for his courtroom antics – threatening to jail him and report him to the state bar.

On two separate occasions, the elderly victim was confronted by thugs who threatened her if she continued to pursue prosecution. Despite this, detectives learned that Szocs provided the defendant with a copy of the investigators’ notes listing the name, address and phone number of the victim and each witness in the case.

At the conclusion of the five week trial, the jury found Gabor guilty on all counts. He was sentenced to state prison and was extradited back to Hungary for prosecution.