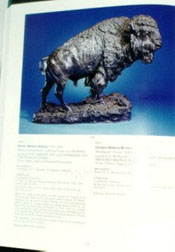

A married couple living in a fashionable home in West Los Angeles received a bronze sculpture of a buffalo from relatives many years ago. It was by American artist Henry Merwin Shrady and was entitled Monarch of the Plains. The bronze had been in the family since the 1930s. It was large and heavy so the couple kept it outside by the back door. Over the years, the owners were vaguely aware that the value of the sculpture had risen but an accurate value was hard to determine because no auction records could be found for the same size sculpture by this artist.

A married couple living in a fashionable home in West Los Angeles received a bronze sculpture of a buffalo from relatives many years ago. It was by American artist Henry Merwin Shrady and was entitled Monarch of the Plains. The bronze had been in the family since the 1930s. It was large and heavy so the couple kept it outside by the back door. Over the years, the owners were vaguely aware that the value of the sculpture had risen but an accurate value was hard to determine because no auction records could be found for the same size sculpture by this artist.

One day, the couple returned home and discovered the sculpture missing. The Art Theft Detail assumed investigative responsibility for the case. There were no witnesses, clues or physical evidence. The owners could not think of anyone who could have committed the theft.

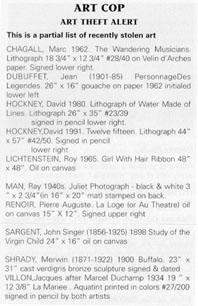

Luckily, the victims had a good quality photograph of the stolen art. With this image and a good description, the detectives sent out art theft bulletins to hundreds of galleries, art dealers, auction houses, and art associations. The case languished for more than a year with no leads.

One of the art bulletins went to the Art Dealer’s Association of California (ADAC). The association included the information in a newsletter mailed out to members. An art dealer was visiting a gallery where he came upon the ADAC newsletter description of the stolen Shrady sculpture. He contacted the detectives because he recalled seeing a similar sculpture at a thrift shop one year earlier.

One of the art bulletins went to the Art Dealer’s Association of California (ADAC). The association included the information in a newsletter mailed out to members. An art dealer was visiting a gallery where he came upon the ADAC newsletter description of the stolen Shrady sculpture. He contacted the detectives because he recalled seeing a similar sculpture at a thrift shop one year earlier.

A detective went to the thrift shop that was owned by a wily old woman who had been in the business a long time. She verified that she bought the sculpture for $50 from a street person named Henry who drove a van. This occurred the day after the theft. However, she claimed she sold the sculpture a week later for $300 to an unknown person.

The detective had a hunch the shop owner was not being entirely candid about the status of the sculpture. Since the shop owner was a secondhand dealer, licensed and regulated by the city of Los Angeles, he decided to review all business receipts for transactions during the time period the shop was in possession of the sculpture. The receipt for the $50 purchase of the sculpture by the shop was located. Other receipts were found, even for sales totaling less than $1. However, no receipt could be found for the $300 sale of the sculpture to an unknown buyer. The thrift shop owner had no explanation for this.

The detective had a heart-to-heart talk with the shop owner explaining the possible repercussions to the owner’s livelihood and freedom if it was learned that she was concealing stolen property. The detective then left to give the shop owner time to think about her options. The following day, the detective was contacted by the shop owner’s attorney who announced that the Shrady sculpture had been “found” in the shop owner’s garage in Malibu. The detective recovered the bronze which was identified from its distinctive verdigris pattern.

Other thrift shop owners were located who remembered Henry trying to sell them the Shrady bronze around the time of the theft. One shop owner thought the sales attempt peculiar enough that he tried to write the license plate number of Henry’s van on a piece of paper. Although he transposed some of the digits while recording the number from memory, the scrap of paper helped to corroborate Department of Motor Vehicle information the Art Theft Detail later obtained.

Other thrift shop owners were located who remembered Henry trying to sell them the Shrady bronze around the time of the theft. One shop owner thought the sales attempt peculiar enough that he tried to write the license plate number of Henry’s van on a piece of paper. Although he transposed some of the digits while recording the number from memory, the scrap of paper helped to corroborate Department of Motor Vehicle information the Art Theft Detail later obtained.

The detective went back to the victims and asked them if they knew anyone named Henry who drove a van. They immediately thought of a handyman who used to work around the house. They recalled how one day, Henry Lightfoot III came to the door of the couple’s home and offered to repaint the house numbers on the curb. The occupants took a shine to Henry and hired him from time to time to paint and do odd jobs around the house. In this way, Henry became familiar with the grounds and what was inside the house.

The couple learned that Henry had an arrest record and was in a substance abuse program at a local VA hospital. They wanted to assist Henry in his rehabilitation by providing him with honest work. However, after learning that he had been released from jail again and was on parole, they told Henry they could no longer hire him. The theft occurred shortly thereafter. Asked why they had never mentioned Henry during earlier conversations with the detective, they said they did not want to point a finger at Henry because they had no proof he had committed the theft.

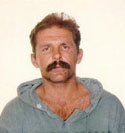

Now, with the correct name, a phone number and a partial license number, the detective was able to positively identify the suspect from photographs. Henry Lightfoot III was a career criminal who had been in prison twice before and had an arrest record for robbery, kidnapping, burglary, forgery, drugs, assault on a police officer, receiving stolen property, and other offenses, and was currently on parole.

Now, with the correct name, a phone number and a partial license number, the detective was able to positively identify the suspect from photographs. Henry Lightfoot III was a career criminal who had been in prison twice before and had an arrest record for robbery, kidnapping, burglary, forgery, drugs, assault on a police officer, receiving stolen property, and other offenses, and was currently on parole.

A warrant was obtained for Lightfoot’s arrest. He was soon arrested during a routine traffic stop. He later pled guilty and was sent back to state prison.

When the bronze was recovered, the victims had already been paid $39,000 from their homeowner’s insurance policy. This was the appraised value at the time. However, during the investigation, the Art Theft Detail learned that another Monarch of the Plains from the same cast had been sold at auction for $123,500 through Christie’s in New York. This alerted the victims that their sculpture was worth far more than they suspected. Although the bronze was now the property of the insurance company, the victims had a provision in their insurance policy allowing them, at their option, to buy back property that is later recovered. As a result, they returned the $39,000 to the insurance company and regained title to art they now knew was worth much more than the insured value.

There was no posted reward for information leading to the recovery of the sculpture. However, the detective contacted the insurance company on behalf of the art dealer who led detectives to the thrift shop where the Shrady sculpture was last seen. As a result, the insurance company graciously decided to pay the dealer a finder’s fee for his assistance in the recovery of the stolen property, which also led to the arrest and conviction of the thief.