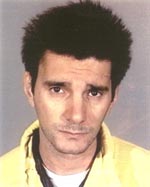

Art cases are often the product of betrayal. Even hardened killers, gang members, and run-of-the-mill thugs usually have an inner focus group made up of a parent, a loved one, or a friend that they will not betray. However, George C. Grimaldis, 32, everyone was fair game. As we will see, George stole from his own family, betrayed mentors and supporters, and fronted his girlfriend and best friend so that their names appeared on transactions involving the sale of stolen art.

Art cases are often the product of betrayal. Even hardened killers, gang members, and run-of-the-mill thugs usually have an inner focus group made up of a parent, a loved one, or a friend that they will not betray. However, George C. Grimaldis, 32, everyone was fair game. As we will see, George stole from his own family, betrayed mentors and supporters, and fronted his girlfriend and best friend so that their names appeared on transactions involving the sale of stolen art.  Those he stole from would have gladly assisted George in becoming a successful art dealer. But George was in a hurry. He wanted now, for free, what it had taken others decades of hard work to achieve.

Those he stole from would have gladly assisted George in becoming a successful art dealer. But George was in a hurry. He wanted now, for free, what it had taken others decades of hard work to achieve.

Everyone thought well of George. He had come a long way from his days as a long-haired, tattooed rock band guitarist in Baltimore where his father owns an art gallery. Now, in Los Angeles, he appeared to be pursuing a family tradition as a respectable director of the Tobey Moss Gallery – a well-established art gallery specializing in Old Master works on paper as well as contemporary art by living artists. After working at the gallery for a year, George had gained the trust of Tobey Moss, the owner, who had grown quite fond of George and given him wide latitude in running the gallery.

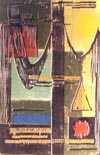

Soon after returning from an art exhibition in New York, Tobey began noticing art missing from her gallery. These included 16th-19th century Old Master drawings, etchings, woodcuts, watercolors, etc., but also included artworks by Werner Drewes, Edward Ruscha, Rockwell Kent, James Gill, Thomas Hart Benton, Francisco Toledo, Louis Lozowick, Rufino Tamayo, Peggy Bacon, Ynez Johnston, Mario Avati and many other artists.

Soon after returning from an art exhibition in New York, Tobey began noticing art missing from her gallery. These included 16th-19th century Old Master drawings, etchings, woodcuts, watercolors, etc., but also included artworks by Werner Drewes, Edward Ruscha, Rockwell Kent, James Gill, Thomas Hart Benton, Francisco Toledo, Louis Lozowick, Rufino Tamayo, Peggy Bacon, Ynez Johnston, Mario Avati and many other artists.

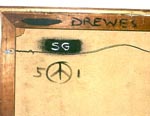

George shrugged off these observations, suggesting instead that Tobey may have forgotten where she placed the art. However, as more and more artworks were discovered missing, suspicion fell on George who found it harder to deflect attention away from himself. After Tobey put pressure on George to produce the missing art, he began to return some of it. He claimed memory  lapses or stated the art had been shown to clients. However, upon closer inspection of the returned art, Tobey noticed there were alterations and obliterations of inventory numbers, estate stamps and prices that would trace the artworks back to the Tobey Moss Gallery. It appeared that some of the erasures were hastily restored in George’s handwriting when he was forced to return this art. On one Drewes painting, the unique inventory number written on the back by the artist was painted over and replaced with the initials “SG.”

lapses or stated the art had been shown to clients. However, upon closer inspection of the returned art, Tobey noticed there were alterations and obliterations of inventory numbers, estate stamps and prices that would trace the artworks back to the Tobey Moss Gallery. It appeared that some of the erasures were hastily restored in George’s handwriting when he was forced to return this art. On one Drewes painting, the unique inventory number written on the back by the artist was painted over and replaced with the initials “SG.”

The Art Theft Detail was contacted and a search warrant was served on George’s residence. More stolen art was found in the trunk of his BMW. Still protesting his innocence, George made a series of statements that were ultimately determined to be false and misleading. Clients who supposedly requested to see the missing art were located and recalled neither seeing the art nor requesting to see it. George claimed he consigned high-value artworks to a new customer but he never got an address or even a business card and “lost” all paperwork and phone numbers necessary to identify the client. George had no explanation for the alterations and erasures on the many pieces of gallery art in his possession.

A rambling, manipulative letter written to Tobey by George had a consignment sheet attached showing that he delivered artworks to a client. However, the signatures turned out to be forgeries and the parties reported having no contact with the art.

A forensic examination of ink obliterations on the artworks revealed the ink matched pens seized from George during the search warrant. A further examination of these obliterations using infrared light revealed a unique estate stamp connecting the artwork to the Tobey Moss Gallery. Some of these crude obliterations were done with a permanent ink marker that bled through the paper, damaging the unique images.

A forensic examination of ink obliterations on the artworks revealed the ink matched pens seized from George during the search warrant. A further examination of these obliterations using infrared light revealed a unique estate stamp connecting the artwork to the Tobey Moss Gallery. Some of these crude obliterations were done with a permanent ink marker that bled through the paper, damaging the unique images.

|

|

|

|

During the initial search of George’s residence, a large number of art reference books were on display. George was asked to select the books that needed to be returned to the Tobey Moss Gallery. George tried to bluff the detectives by giving them only two books, claiming the remaining volumes were his. However, the library was photographed and Tobey identified many books as gallery property. The detectives returned to George’s residence with another search warrant and seized the remaining volumes, identifying them through gallery stamps, personal dedications, inventory numbers, and personal annotations made by Tobey.

The investigation revealed that during the time period of the thefts, George intended to quit his position at the Tobey Moss Gallery and open his own art gallery. He found a German partner but needed to quickly raise several hundred thousand dollars. This was accomplished by systematically looting Tobey’s gallery. Losses are estimated to be $500,000.

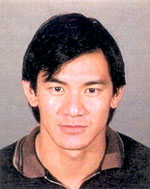

Months after George’s arrest, a break came in the case when Tobey spotted dozens of her artworks for sale in a Swann catalogue in New York. With the cooperation of Swann, the Art Theft Detail traced the artworks to Randy Shaw, an art dealer in Georgia. Randy turned out to be a bona fide buyer who was sold the art by a Pasadena resident named Sean Chunyu Ching, 32.

Months after George’s arrest, a break came in the case when Tobey spotted dozens of her artworks for sale in a Swann catalogue in New York. With the cooperation of Swann, the Art Theft Detail traced the artworks to Randy Shaw, an art dealer in Georgia. Randy turned out to be a bona fide buyer who was sold the art by a Pasadena resident named Sean Chunyu Ching, 32.

The detectives immediately recognized the name. They had interviewed Sean soon after George’s arrest when they learned that Sean had written more than $60,000 in checks to George during the time of the thefts. During an interview with detectives at his home, Sean claimed that none of the money was connected to the sale of art and that he had never sold or received art from his best friend, George Grimaldis.

With the assistance of Randy Shaw, detectives tape-recorded several phone calls with Sean who claimed that he and his “brother George” were selling the art for their father. This evidence, along with a search warrant on his residence, revealed Sean to be George’s cohort in crime – a knowing and willing accomplice who continued selling art stolen from Tobey for over a year after the thefts occurred.

Sean turned out to be a struggling actor who lived with his parents to make ends meet. His occasional acting jobs included doing skits as Spiderman at Universal Studios. However, this spider soon got caught in his own web of deceit.

Sean decided he could beat the case if he took it to trial. When asked on the witness stand whether he had been an actor, he grandly announced, “I AM an actor.” However, his performance in court did not win him an Academy Award. Instead, he obtained a felony conviction for grand theft and receiving stolen property. He didn’t realize that memorizing a prepared script is of less value on the witness stand than the ability to improvise – especially if you’re trying to hoodwink the court. Sean was constantly tripped up by the discrepancies, fallacies, and implausibilities of his explanations.

During the five-week trial, Sean fell into a trap set by the prosecutor. He was given the chance to comment on a crime alert on the Grimaldis case that appeared on the LAPD Art Theft Detail website. The alert came out months before Ching was identified as a suspect in the case. Ching took the bait and went into a diatribe about his distaste for the contents of the alert when it came out. It was soon brought to his attention that the alert contained details of the case that he had earlier professed ignorance of. The alert also contained images of many of the stolen artworks Ching had handled that were later traced to him. Ching had to admit that he willingly continued selling stolen art for Grimaldis after receiving information that should have alerted him that he was embroiled in a continuing criminal enterprise.

Faced with an avalanche of evidence against him, George Grimaldis pled guilty to the charges against him. However, during the Ching trial, new evidence was uncovered that revealed George had victimized more galleries.

After his arrest, George’s first call was to Jack Rutberg, the owner of another art gallery in Los Angeles. George had been working for both the Tobey Moss Gallery and Jack Rutberg Fine Arts at the same time without either owner knowing it. Rutberg had high regard for George and could not believe that he was capable of stealing art. As a show of support, Rutberg obtained a Beverly Hills attorney for George as well as assuring George that he could continue working at Jack’s gallery when he bailed out of jail.

During the course of the investigation, Rutberg repeatedly denied being the victim of an art theft. However, upon receiving a subpoena to testify under oath, Rutberg finally admitted that his gallery had also been looted. Over $212,000 in art was stolen during the brief time that George worked for Rutberg. This included a $45,000 artwork by Henri Fantin-Latour that was traced to the art dealer in Georgia. Rutberg informed George’s attorney about the theft. Soon, about a dozen artworks were mailed back to Rutberg anonymously. George’s father reimbursed Rutberg for the rest of the stolen art. Rutberg also revealed that George had offered his gallery an expensive Alice Neal painting, representing it as his own. He later learned the painting was a consigned artwork that disappeared from the Grimaldis Gallery in Baltimore.

During the course of the investigation, Rutberg repeatedly denied being the victim of an art theft. However, upon receiving a subpoena to testify under oath, Rutberg finally admitted that his gallery had also been looted. Over $212,000 in art was stolen during the brief time that George worked for Rutberg. This included a $45,000 artwork by Henri Fantin-Latour that was traced to the art dealer in Georgia. Rutberg informed George’s attorney about the theft. Soon, about a dozen artworks were mailed back to Rutberg anonymously. George’s father reimbursed Rutberg for the rest of the stolen art. Rutberg also revealed that George had offered his gallery an expensive Alice Neal painting, representing it as his own. He later learned the painting was a consigned artwork that disappeared from the Grimaldis Gallery in Baltimore.

George Grimaldis was sentenced to five years in state prison.

Much of the stolen art is still unaccounted for. If you have any information about this case or are aware of art sold by Sean Ching or George Grimaldis, please contact the Art Theft Detail at 213-486-6940.